By Peter Silkov

Of all sportsmen, it is the boxer who seems to live most precariously on the edge, often both in and out of the ring. Inside the ring, they take part in what is the most basic activity known to man; using their fists to hit the opponent standing in front of them. Everyone who knows even a little about boxing understands that there is so much more to it than just what meets the eye. It is about mental strength, spirit, and courage. It is about having the ability to put yourself on the line, and face down the kind of fears and thoughts of self-preservation which keep the average man from ever stepping foot competitively between the ropes. Many fighters seem to live the same way out of the ring that they do inside it, wrapped up in a cloak of danger and drama.

This is one of the many attractions of the boxer. These are men who do not generally live their lives quietly or safely as the rest of us do. Perhaps here we have the reason why so many boxers have been the subject of biographies, and why Hollywood has always been so fascinated with the boxer in film, from “The Champ,” to the “Rocky” films. Yet, despite all of the action that takes place inside the ring, it is the life outside of the ropes, real everyday life without gloves on, which often proves to be far more dramatic and traumatic, than anything Sylvester Stallone has dreamt up for his famed ‘Rocky’ movies. Bobby Chacon lived a kind of life that was straight out of a Stallone or Martin Scorsese film; a roller coaster ride of more ups and downs than one person should be expected too deal with and remain in one piece.

Like many that later find their way into boxing, Chacon grew up amid domestic strife. His father left when Bobby was very young, and by the time he was a teenager he was involved in a street gang and finding himself drawn into numerous street fights and petty clashes with the police. As his life descended into the chaos of the street, Chacon met Valerie, the person who would have a profound influence upon the rest of his life, an influence both hugely positive, yet, ultimately tragic. Valerie would become Bobby’s wife and a guiding light that would lead him from the street onto a path which would take him on to glory and stardom. It was Valerie who told the street fighting Chacon that he should take his fighting inclinations to a boxing gym where they could be of more legal use. Bobby obeyed and a short, but successful amateur career ensured.

He was a natural, and like all such fighters, the armatures couldn’t satisfy his ability for long. Bobby turned professional in April of 1972, at the age of twenty-one, picking up the nickname “Schoolboy” due to his youth and baby-faced features. Despite those youthful features and a ready smile, Chacon could fight.

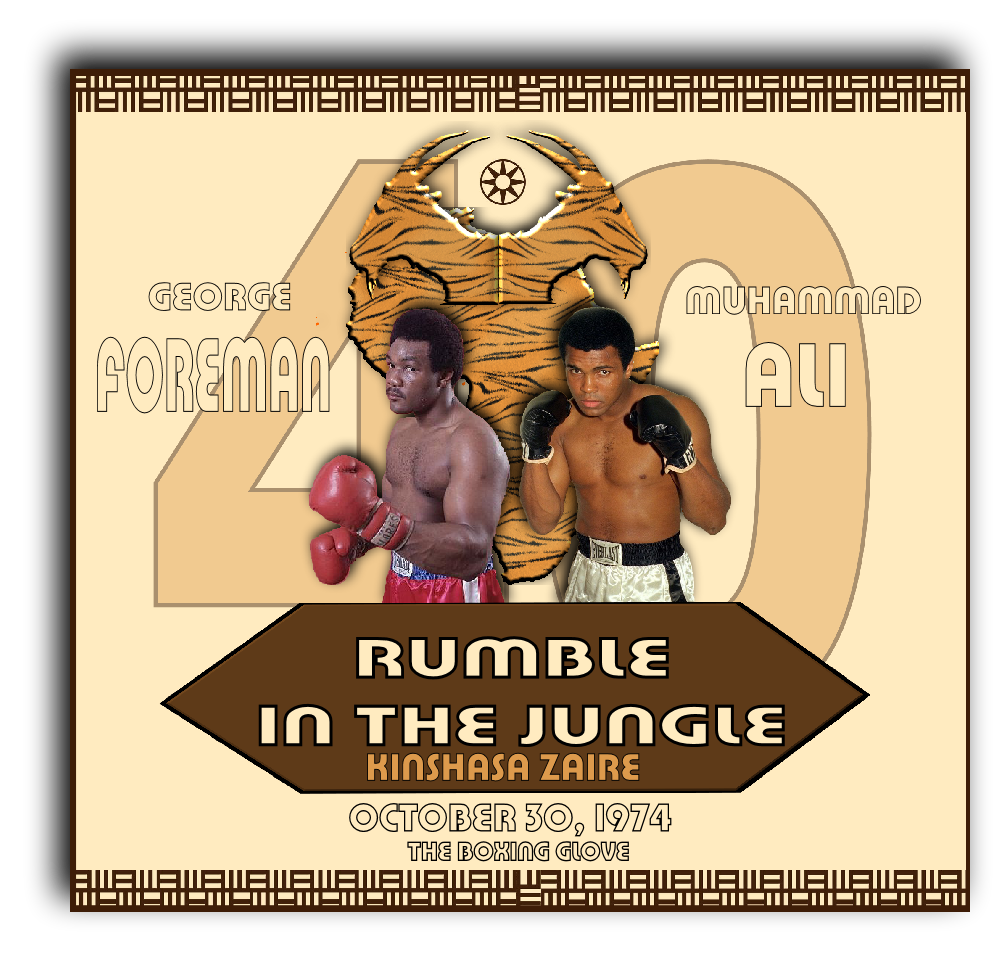

The early 1970s were a time when boxing was enjoying a spectacular boom of both popularity and talent that seemed to have started with the rise of Muhammad Ali in the early 60s and slowly spread throughout every weight division within the sport. Boxing was booming, but while it was a great time to be part of it all, it was also one of the toughest; there were few easy rides to the top. Young talented prospects had to fight it out amongst themselves. Success only came from hard work and hard fights.

Bobby Chacon certainly had no easy ride. His first professional opponent, Jose Antonio Rosa, was unbeaten in seven fights, and Bobby knocked him out in the 5th round. Within four months and 11 fights, Bobby was already a main event fighter.

As a boxer, Bobby had it all, along with his youthful good looks, and charismatic personality outside of the ring. Inside the ring, Chacon had a mixture of angelic boxing skills, coupled with a devilish offence. Bobby was the perfect boxer-fighter, mixing speed, technique and power, and an inclination to go toe-to-toe even when he could have played it safe and rely more on his boxing skills. Unsurprisingly, the fans loved him from the beginning. In the 1970s, the West Coast was a hotbed of activity for the lighter weight divisions, and Chacon was another talented addition to a pool, which was literally overflowing with gifted and exciting fighters.

By early 1973, after barely a year in the professional ranks, Chacon had broken into the worlds top ten, with wins over top contenders Arturo Pineda, Frankie Crawford, and former world champion Chucho Castillo. The Schoolboy was a sensation, but on June 23, 1973, he suffered his first professional set back when he was stopped after 9 rounds by former World bantamweight champion Ruben Olivares. Looking back today it seems incredible that Chacon could be put into the same ring with the already legendary Olivares, who had a record of 71-3-1, with 63 knockouts, after only nineteen fights, and one year as a professional. Although Olivares had left his best days behind him in the bantamweight division, against Chacon, he proved that he was still a very formidable fighter at featherweight. Yet, Chacon gave the Mexican idol all he could handle for much of the contest, which turned out to be an epic toe-to-toe classic, the kind of war that would become a habit for Chacon, and a defining feature of his career. In the end, Olivares’ extra strength and experience proved to be the difference, and The Schoolboy was pulled out of the fight after the 9th round, by his trainer/manager Joe Ponce.

Back in the days when a fighter was expected to fight his way into title contention, Chacon’s loss to Olivares was a setback rather than a disaster. He bounced back almost immediately, more experienced and a little wiser, and with his trademark grin intact. Over the next nine months, Bobby put together four wins, stopping Jorge Oscar Ramos in 10 rounds, knocking out Jose Luis Martin Del Campo in 9, then halting Ramos again, this time in 5 rounds, before stopping Genzo Kursosawa in the 9th.

On May 24, 1974, Chacon came face to face between the ropes with another rising star of the featherweight division, Danny “Little Red” Lopez. It was no surprise that the red-headed Lopez with his Irish-American Indian descent, and Chacon, with his part Mexican heritage, would go together so well in the ring. This was the type of fight that would probably take years in the making today, but back in the 1970s, clashes like this were the accepted rite of passage for rising young contenders and budding future champions. Lopez entered the ring with an unbeaten record of 23-0, with 22 of his victories by knockout. If anything he had an even better punch than Chacon. For once, the fight lived up to all of the hype, with the fighters treating the Los Angeles crowd to one of the classics of the decade, as both men stood toe-to-toe and traded bombs from the start. It was an electric spectacle as each man displayed his spirit and talent, in a clash that was the fistic equivalent of two young rock guitarists dueling against one another on stage. The fight ebbed and flowed, but in a performance, which in hindsight has to be seen as one of the most outstanding of his career, Chacon’s extra speed and skill gave him a crucial edge over Lopez, wearing him down, and finally overwhelming him in the 9th round. This was a night where Bobby put it all together and displayed the kind of defensive skills and boxing technique, that few today realize he had before the all-out slugging, ‘Rocky’ incarnation of his later career.

Four months later, Chacon was a world champion, knocking out the big-punching Alfredo Marcano in the 9th round, for the vacant WBC world featherweight championship, in front of his adoring fans at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium.

Chacon was still only 22 years of age and had the boxing world at his feet. Even in the ultra-competitive and talent-laden 126-pound division, he looked a sure bet to be world champion for some time. The glow of greatness seemed to be shining upon him. Yet, it is a well-known irony in boxing, that for all the trials and tribulations involved with a fighter making his way to the top, it is far harder for him to stay there once the summit has been reached. Aside from all of the hungry contenders eager to pull a champion back down to earth, there are also the out of the ring factors that often come into play when a fighter finds fame and fortune; namely, the hangers-on, the late nights, the fast cars, and the faster women. Soon after winning his world title, Bobby began partying with the same enthusiasm and energy that he usually displayed inside the ring. In the midst of a gathering whirlwind of fame and success, Bobby fired Joe Ponce, the man who had guided him in the ring since his amateur days. Like so many others before and after him, Chacon was quickly losing touch with what had taken The Schoolboy to the top in the first place.

Six months after winning his world title, Chacon made his first defence on March 1, 1975, knocking out Jesus Estrada in the 2nd round. For a young champion driving ever faster in the fast lane, it was coming all too easy for Chacon at this point, but the big crash was looming. On June 20, three months after the Estrada defence, Chacon put his title on the line against his old adversary, and the only man to beat him so far in his career, Ruben Olivares. Olivares had already won and lost the WBA version of the world featherweight title, since the pairs first encounter, and despite being a party animal himself, was still a very dangerous fighter.

Given his shot at Chacon’s WBC championship, Olivares came in as fit as he could be, while for Chacon, the party was about to end. One week before the fight The Schoolboy was 15 pounds overweight. Although he made the weight on the day of the fight, Chacon was pale and drawn, and having seen the champions condition, a confident Olivares predicted a knockout in one or two rounds. Chacon was stopped in the second round, after being floored twice; his weight weakened body defenceless. Almost in a blink of an eye, the world title was gone. As Chacon would later say himself “I had it all and I threw it all away.”

After the big party, came the long hangover, and like most hangovers, it lasted longer than the party that preceded it. Bobby’s hangover would last for the rest of his career. No longer a world champion, and with his reputation stained, Chacon fell almost immediately into boxing’s version of the twilight zone, fighting journeymen and rising contenders for a fraction of the money he had commanded prior to losing his title. Worse still, having moved up to the junior-lightweight division, he turned up for these fights under-trained and under-motivated. On December 7, 1975, Chacon was out-pointed by the then unknown Rafael “Bazooka” Limon, in the first of what would be four brutal wars between the two men. Limon was a raw, face-first, southpaw, with a big punch, who was seemingly impervious to either punishment or pain, and he and Bobby would share a fistic feud of almost unmatched pugilistic savagery.

At just 24 years of age The Schoolboy was already being written off as a ‘has been’ by many observers; another of boxing’s burn out cases. The fans still loved to see him fight, that would never change, but the talent that had once flowed in such an exciting manner had been reduced to a splutter. Now, when Chacon went toe-to-toe it was not simply due to his innate love of a slugfest, but because his legs could no longer carry him like they used to do, and his reflexes were no longer as fast or as sharp. Now he was having wars against fighters that just a little while before, he would have handled with ease.

Two months following the Limon defeat, Chacon was floored twice and bloodied badly by journeyman David Sotelo. Despite gaining the decision, in his dressing room after the fight, a battered Chacon was begged by his wife Valerie to retire. It would be the first of many such scenes between Bobby and his wife. With a terrible irony, the person who had first inspired Bobby to take up boxing, couldn’t bear to see him fight anymore, especially now with his talent faded, and the fights getting harder and harder.

He managed to stay out of the ring for nine months after the Sotelo fight, but Chacon was back at the end of 1976 with two wins. By now, Chacon was filled with the pain of unfulfilled potential, but his drive to recapture what he had lost was torn between his wife’s pleas for him to retire and his ongoing penchant for the fast lane.

Ironically, in late 1976, Chacon’s old rival Danny Lopez had won the WBC world featherweight championship and would remain champion until 1980. His career had become a telling contrast to that of the man who had beat him just a few years before.

In 1977, Chacon made a concerted effort to get back where he had once been, fighting six times, he won all but one, including a belated point’s victory over Ruben Olivares, himself now an ex-world champion struggling to stay in contention. However the year ended with Chacon losing a split point's decision to Arturo Leon, and Bobby’s resurgence was halted.

After losing to Leon in November 1977, Chacon took six months out, then fought just three times in 1978, winning them all, but getting no closer to a chance at gaining a world title shot.

Two more wins in 1979 came, along with a controversial 7th round technical draw with Rafael “Bazooka” Limon, in what was the pair’s second fight. This match served to make the pair’s rivalry more bitter than ever after the fight was ended in the 7th due to a severe cut on Limon, caused by an accidental head butt. The controversy fanned the flames of a mutual animosity.

Then on November 16, 1979, Chacon was granted a shot at Alexis Arguello’s WBC world Junior lightweight championship. Showing glimpses of his former brilliance, Chacon started brightly and took a point’s lead over the first five rounds. Then in 6th, an Arguello punch opened up a two-inch gash in the corner of Chacon’s right eye, and in the 7th, Arguello took control of the fight, as the bloody and tiring Chacon was forced to take a count. Between rounds, the doctor stopped the fight, and with it, Chacon’s chance of fistic redemption seemed to have gone forever.

Four months later, on March 21, 1980, Chacon met Bazooka Limon for the third time, in what turned out to be their most ferocious fight so far. Although he emerged from the brutal clash a points’ winner after ten rounds, Chacon had looked sluggish and out of sorts, and had shipped a tremendous amount of punishment. The decision was close and controversial, and at the end of the fight Chacon was battered and bloody, with his eyes swollen and cut. It was a look that he would wear with increasing regularity throughout the remainder of his career.

After the third Limon battle, Chacon stayed away from the ring for 10 months, but the temptation to recapture unfulfilled potential is irresistible, as is the urge to hear the roar of the crowds once again. Despite Valerie’s pleas, Bobby couldn’t keep away, boxing was all he knew. So he returned again, with two wins in early 1981, and was given a shot at Cornelius Boza-Edward’s WBC world junior lightweight championship (Alexis Arguello having vacated the title and moved up to win the lightweight championship.)

Edwards was a big-punching southpaw, who had captured the title from Chacon’s old nemesis, Rafael Bazooka Limon, after a brutal slugfest. Boza-Edwards had been born in Uganda, and brought up in England, but had found his boxing home in America, where his own inclination for fistic warfare had gained him the nickname “Mr. Excitement” amongst the American media.

With Boza-Edwards, the younger and fresher fighter, Chacon went into their clash as a clear underdog. Yet, seeing an unexpected chance of world championship glory within his grasp once more, Bobby shocked the so-called experts, who considered him washed up, rolled back the years, and gave Edwards a savage war. The two men stood face to face for much of the fight, breathing in each other's breaths, and exchanging physical punishment with an almost maniacal glee. Bobby gave as good as he got for the first 10 rounds and even looked at times like he might turn back the clock completely and pull off an upset win. It was a fight straight out of Rocky.

Chacon still had a vestige of the silky skills that had taken him to the top almost a decade earlier, the jab, the left hook, and that right hand. Bobby showed, in flashes against Boza, the fighter he had once been not so long before. However, from the 10th round onwards, Boza-Edwards youth and conditioning saw him take control of the match. By the 13th round, Chacon was bloodied and tired and taking a beating, while Boza rained punches upon him in an effort to stop him. Though he was dazed and spent, Chacon refused to go down and continued to try and fight back.

When Chacon’s corner stopped the contest after the 13th round, it looked to be the end, not only of the fight but also of The School Boy’s career. He had given it one more shot and gone down to a defeat that was glorious in all its gory violence. Chacon had lost like a warrior. Surely he would hang up his gloves for good and retreat to a quieter life with Valerie and the kids. However, never one to take the easy road, Bobby didn’t want the song to end yet. The battle with Boza had awakened something inside Chacon. Amid all of the heavy blows, the blood, and the bruises, he too had felt those flashes of past brilliance; the echoes of his lost youth and past glory. Chacon felt that if he had been better prepared physically he would have had a good shot at beating Boza-Edwards in their fight.

Six months after losing to Boza-Edwards, Chacon stopped Augustin Rivera in 6 rounds. He had reunited with Joe Ponce and at 30 years of age was talking about fighting regularly again in a final drive for one more title shot. It was too much for Valerie. Just when she had thought it was coming to an end, Bobby was starting up all over again, fighting every other month, often against men who had still been in school when he was a world champion.

During the build-up to his fight with Salvadore Ugalde, on March 16, 1982, Valerie begged Bobby not to go through with the match. As always Bobby was torn, he loved his wife and family, but the pull of the ring was undeniable and unavoidable, and as deeply embedded within him as his love for his family. On the day of the fight, Valerie took a loaded rifle, put it to her head and pulled the trigger. That same night Chacon stopped Ugalde in the 3rd round and then wept uncontrollably in the arms of his cornermen.

In a life already laden with irony, Valerie’s suicide left Bobby with far more reasons to carry on boxing, rather than stop. In many ways, Boxing was all that he had left. He was no longer torn. Her death also pushed Bobby straight back into the spotlight; he was no longer just another ex-champion chasing the shadows of the past, but the main player in a modern tragedy.

Chacon scored two more wins, stopping Rosendo Ramirez in 8 rounds and out-pointing Arturo Leon over 10. Then on December 11, 1982, he faced Rafael Bazooka Limon for the fourth time and this time with Limon’s WBC world junior lightweight championship the prize for victory. In the months previously, Cornelius Boza-Edwards had lost the WBC title in an upset to Rolando Navarrete, who had then been beaten by Bazooka Limon. Sylvester Stallone could not have dreamed up a better plot. Now Bobby was to have his final shot at glory and redemption, against the man who had become his arch rival over the past half-dozen years.

With an almost hysterical Sacramento crowd looking on, Chacon and Limon waged a fight that almost defies description for the drama and intensity and non-stop action that it produced. Both fighters seemed to reach deep into their own souls in a way that only boxers can sometimes achieve. While at times it seemed as if the vociferous crowd was powering both men on, at other moments it looked as if each man had become oblivious to everything surrounding them, save for the man standing in front of him in the ring. Both boxers seemed to give and receive an amount of punishment that was almost surreal. The fight had no fairytale beginning for Chacon, as the usually slow-starting Limon begun well, landing his southpaw jab and his left hooks upon The Schoolboy with alarming ease. Chacon was floored in the 3rd round, albeit briefly, as the omens seemed to point against a victory for the aging “Schoolboy.” However, as the fight progressed, despite all of the punches he was landing upon his challenger, Chacon kept coming at Limon. As the fight passed its halfway point it was Chacon who was growing stronger, while Limon was beginning to wear the look of someone asking himself why the man in front of him is still standing.

Even when he was knocked down again in the 10th round, Chacon didn’t retreat, if anything, the knockdown seemed to make him even stronger and more determined. Both fighters were bruised and bloody now, but it was Chacon who looked to be gaining strength, as Limon’s attacks seemed to be growing tired and desperate. After fighting evenly through the 11th and 12 rounds, Chacon miraculously rallied over the last three rounds, as Limon began to slow under the weight of exhaustion.

Bobby was a man inspired, fighting like someone who refused to be beaten. In the 15th and final round, two overhand rights by Chacon floored Limon, and although Bazooka beat the count and made it to the round’s end, the fight had been sealed. The point’s verdict for Chacon was 142-141, 141-140 and 143-141.

Chacon was world champion again after almost a decade in the wilderness and the fight was voted Fight of the year for 1982 by the Ring magazine. It was one of the final fights set for fifteen rounds, and one of the best examples of what a 15 round title fight could produce.

Despite his wonderful victory, and the plaudits that came his way in its aftermath, Chacon’s success was bittersweet. He had made it back to the top like he had wanted, but he had lost Valerie along the way.

Unfortunately, Chacon’s second reign as world champion was soon mired in controversy when he fell into dispute with promoter Don King over a proposed defence against rising star Hector “Macho” Comacho. King claimed he had a signed contract for Chacon to put his title on the line against Comacho, but Chacon denied the validity of the contract and when offered more money to defend against old foe Cornelius Boza-Edwards, took the Edwards’ fight instead. Chacon defended his world title against Edwards on May 15, 1983.

It was almost two years since the pair had first met in the ring, and with Chacon now two years older and coming off the incredible war with Limon, few gave the aging champion much chance of retaining his title against the younger and seemingly stronger Boza-Edwards. Incredibly, Chacon once again dug deep into his inner reserves and produced a performance that seemed to transcend his physical limitations. The fight itself was another savage and bloody affair, one where the two fighter’s ability to punish each other and withstand punishment themselves, becomes something peculiarly artistic, like a brutal and bloody ballet.

Chacon floored Boza in the first and second rounds but was floored himself in the 3rd round. By the halfway mark, Bobby was badly cut over both eyes and spending much of his time on the ropes, absorbing Boza-Edwards heavy, slashing punches. Every time it seemed that Chacon was about to be overwhelmed by his challenger, he would fight back and shake Boza with punches of his own. The champion also had to survive a number of inspections by the ring doctor of his severely lacerated eyes. Somehow the fight was allowed to carry on, and as it traveled into the late rounds, just as he had against Bazooka Limon, Bobby began to wear down Boza-Edwards. The 12th and final round was like something straight from a Rocky film, as a swollen and bloody Chacon floored the tiring Boza-Edwards, having the challenger rubber-legged and exhausted by the finish. Chacon retained his title with a point’s victory of 115-113, 115-112 and 117-111. It was another seemingly miraculous performance from Chacon, in a fight that was voted fight of the year for 1983 by the Ring magazine, making Chacon one of the few boxers to win ‘fights of the year’ in two consecutive years. Yet, Bobby’s triumph was soon taken away from him when the WBC sided with Don King in his contractual dispute with Chacon. On June 27, barely five weeks after his victory over Boza-Edwards, Chacon was stripped of his WBC world junior lightweight title for his failure to defend it against Hector ‘Macho’ Comacho. Despite the fact that Boza-Edwards had been rated the WBC’s number one contender, when Chacon defended against him, while Comacho had been ranked at number three. The WBC or any other boxing organization has seldom let logic or fairness stand in the way of its political or financial interests.

Shorn of his world title once again, Chacon was advised to retire by those close to him, but the cheers of the crowd are always a hard habit to break, and perhaps the greater the cheers have been, the harder it becomes to walk away for the final time.

Eight months after the Boza-Edwards epic, Chacon moved up to the lightweight division and on January 14, 1984, challenged Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini for the WBA world lightweight championship. From some angles, this match looked to be a ‘dream fight’ with two of the game’s most popular and exciting fighters squaring off against each other in a fight that was destined to be ‘fan friendly.’ However, from the first bell, it was plain that Mancini was far too young and strong for the sluggish-looking Chacon, who suddenly betrayed every one of his 32 years. The action took place mostly in a corner, with Chacon pinned against the ropes, and while both men were firing punches at one another, Chacon’s seemed to be simply bouncing off Mancini, while Mancini’s shots were rocking the challenger to his toes. By the third round, Chacon was already battered and bloodied around the eyes, and taking repetitive blows to the head, and referee Richard Steele who had worked Chacon’s last fight with Boza-Edwards had seen enough; stepping between the boxers, and ending the fight.

The Mancini fight was the end of the big time for Chacon and should have been the final time he entered the ring, but like so many others, Bobby couldn’t say no to the call of the ring. Chacon wasn’t fighting for world titles anymore; he was just fighting for the sake of fighting.

He had remarried, but he would never get over Valerie, and the marriage ended in acrimony. Perhaps, in the end, the ring was the only place where Bobby felt safe. Over the next four years Chacon would fight seven more times, and despite his faded skills and advancing years, would win all of his fights. Incredibly, amongst those seven wins, he was able to post victories against Carlton Sparrow, Arturo Frias, Freddie Roach, and Rafael Solis. Despite the fact that his legs and balance were just about gone, and his reflexes were just a memory, Bobby retained the instincts of a fighter right up to the end. That and his heart, and an amazing will to win.

After stopping the fancied Rafael Solis in 5 rounds on October 4, 1985, Chacon seemed to slur his words in his post-fight interview. There would be just two more fights in the ring. On June 23, 1987, in his first fight in over 18 months, Chacon was floored 3 times in the first two rounds before fighting back to stop Martin Guevara in the 3rd round. Twelve months later, Chacon swung and shuffled to a ten round point’s win over Bobby Jones. It was finally the end. The heart was still willing, but the body was no longer there.

Since his retirement, Bobby Chacon’s life hasn’t had a happy ending. He has suffered further tragedy, with the loss of a son in the early 1990s to gang violence. Chacon has also been diagnosed with pugilistic dementia, the dark hangover of all the many ring wars for which he became so famous. He has also seen his finances dwindle away into nothing.

Bobby Chacon’s life is a bittersweet tale of incredible achievements against the odds, alongside the tragic consequences of those same achievements. Sometimes it is hard to justify one’s fascination with boxing when even the best of this hard and unforgiving pursuit winds up with the physical cost of their profession.

Perhaps Bobby was not born to live a safe nine-to-five life, wrapped in the cotton wool of the mundane and mediocre. Without boxing, the chances are that Chacon would have come to harm one way or another much earlier in life. Due to his boxing career, Bobby has carved out a formidable legend that will linger for as long as boxing itself does.

Today Bobby Chacon is still beloved by the boxing public, a fighter who embodied all that was dramatic and exciting within the game. His life and fighting career remain both darker and more spectacular than any film script yet created by a Stallone or Scorsese. Most importantly for his fans, Bobby Chacon was real, a fantastic fighter, with incredible gifts, but also a human being, with human failings.

In a world of so many, Bobby Chacon is one of the comparative few to make his mark in something during his life. Perhaps, in the end, that should be enough.

Copyright © 2014 The Boxing Glove, Inc. Peter Silkov Art. All Rights Reserved. Peter Silkov contributes to

www.theboxingglove.com and

www.theboxingtribune.com